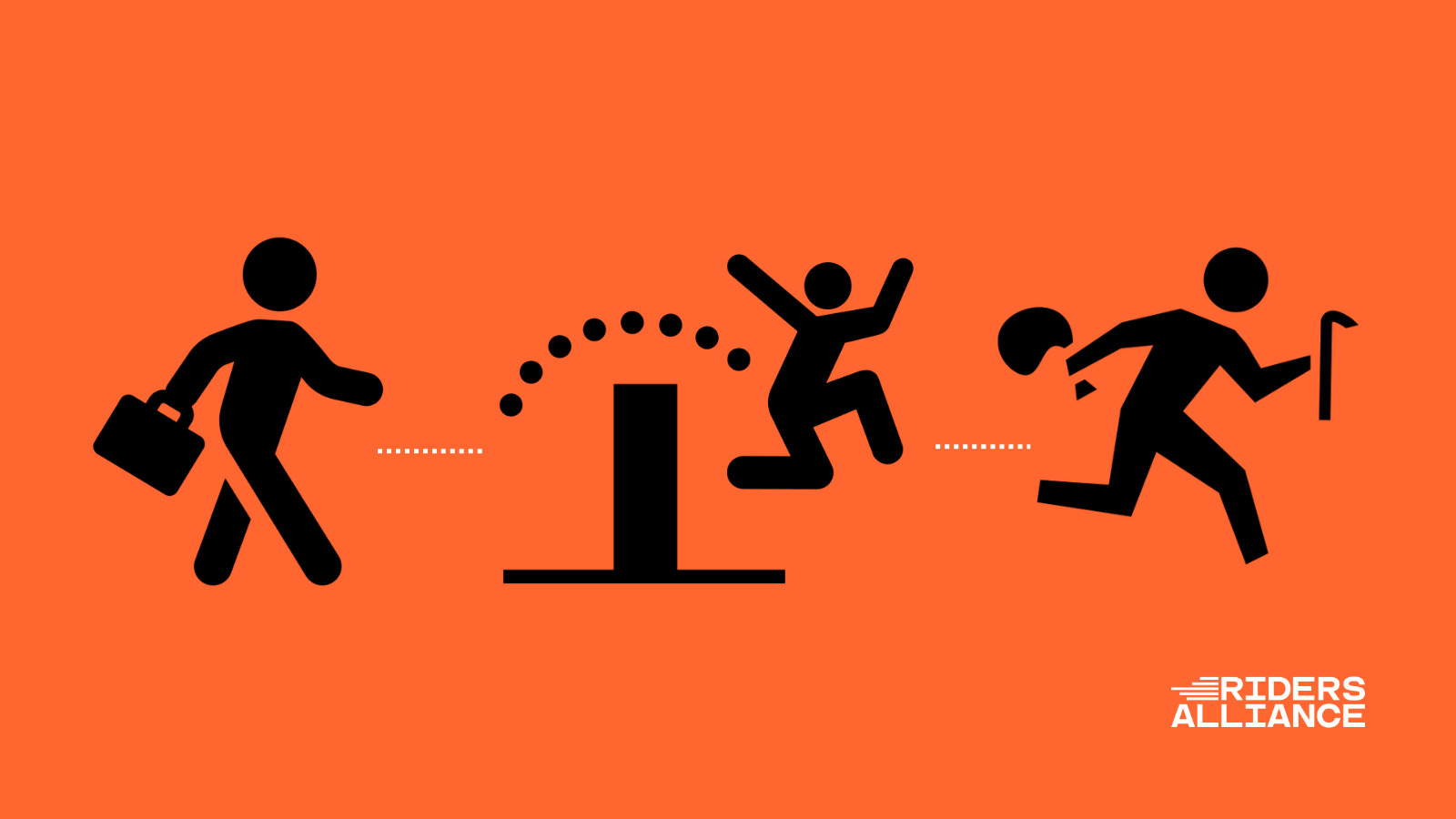

Fare evasion is a fake problem. There, I said it.

The MTA has been talking about fare evasion a lot lately. Like, a lot a lot. And in a way that sometimes feels like turnstile jumpers are the single biggest threat facing our transit system. So big a threat that MTA CEO Janno Lieber has brought together a “blue ribbon panel” to discuss solutions to this issue that, as Mr. Lieber put it, is a “threat to the spirit” of New York that “tears at our social fabric”.

Yikes, that does sound pretty serious. But exactly how serious is it, and what can or should we do about it? How about we take a lil’ dive into this whole fare evasion thing and see exactly what the deal is here.

1: Is fare evasion a problem?

That’s a good question. The answer to which, as it turns out, mostly depends on who you ask. If you ask subway riders, they don’t seem to care much about it at all, which is in stark contrast to CEO Lieber’s insistence that paying riders “feel like suckers” when witnessing fare evasion. In fact, when asked, what riders said they are concerned about are improvements to service, accessibility, safety, cleanliness, bathrooms, and, lowering the cost of transit. So why is the MTA so obsessed with convincing riders that fare evasion is, indeed, a huge problem?

Well, to be fare (c’mon, just let me have one), transit fares are an important operating revenue source for most transit agencies around the country. The problem in New York, though, is that the MTA has a particularly existential stake in making sure that everyone riding transit pays to use it. Unlike most transit agencies around the country that typically generate about 15%-20% of their operating revenue from collecting fares, the MTA relies on fares to cover a whopping 40% of their annual operating revenue.

Did we mention the MTA runs the largest, most expensive transit system in the country, with an operating budget of approximately $18.5 billion in 2022 alone? Because that’s important considering nearly half of it comes directly out of riders’ pockets. It also leads us to the next part of this equation—is fare evasion the actual problem we should be addressing here?

2: No. No, it is not.

I’mma keep it straight with you—fare evasion is not a problem, at least not as it is being framed. What is a problem are poorly funded public services that require end users to keep the agency running those services fiscally solvent year after year with fares collected at the rendering of those services. Now, if you’re the MTA, obviously the prospect of losing half a billion dollars in a year due to fare evasion is a very big problem, but that’s only because those fares are quite literally what’s keeping the lights on.

The current absolute necessity of collecting fares makes it easier to understand why the MTA is so willing to take farcically counterintuitive measures to curb fare evasion, like prohibiting rear-door boarding on NYC buses after spending untold millions installing electronic fare boxes at the rear doors of every single bus.

Did we mention that New York City has the slowest buses in the nation and that all-door boarding has been proven to improve bus speeds and overall travel times?

A more insidious example of the negative effects of the MTA’s obsession with fare evasion, a victimless, nonviolent offense, mind you, is that it increases otherwise unnecessary rider interactions with the NYPD. At best, this could burden a rider, who may be one of the hundreds of thousands of poor New Yorkers struggling to afford transportation costs, with a $50-$100 fine. At worst, NYPD enforcement, which more often than not targets Black and Latino riders, may turn the ultimately negligible act of fare evasion into a needlessly provoked violent encounter, arrest, or may even initiate criminal proceedings that can result in deportation, all over $2.75.

Even worse, it seems the MTA is engaging in a concerted effort to dismiss, or entirely erase, the reality of fare evasion borne from necessity. For example, the MTA has no problem pointing out that the Bronx has the highest rates of fare evasion. But, what they’ve yet to openly acknowledge is that more than 1/5 Bronx residents reported they often have difficulty paying transit fares, the most of all five boroughs. This clearly doesn’t align with the image of fare dodgers the MTA needs us to internalize, so what did they do? The MTA went full propaganda mode and selectively edited footage of a rider attempting to pay their fare before ducking underneath the turnstile. There’s no reasonable explanation for this other than a clumsy attempt to project an image of a “typical fare evader” that would draw the ire of riders and recruit them into their anti-fare evasion crusade. It’s actually kinda wild.

We could go on, but bottom line: instead of blaming riders for failing to fill the operating deficit of the MTA and the public service they operate with their fares, why not just fund the public service? With, like… taxes?

3: Genius ideas the MTA, Governor, NYS Legislature, and NYC Council can have for free

There are plenty of revenue sources we could be tapping into or creating to provide steady, reliable funding for the MTA—enough to alleviate the need to go after fare evasion like it’s the crime of the century. For example:

Flip the NYS gas tax. It generates hundreds of millions of dollars a year, but most of it goes to building and repairing roads, with only a fraction going to the MTA or its operating budget. If we flipped how much revenue went to the MTA, we could generate $500+ million a year for transit operation (wait, how much did MTA say fare evasion will cost them this year, again?). Unfortunately, Governor Hochul recently suspended the gas tax, which will cost the MTA approximately $350 million, or 126 million jumped turnstiles, in revenue this year.

Improve service. Improving riders’ experience in the ways they’ve identified matter to them the most, like faster trips (#6MinuteService) and improved accessibility, is key to increasing ridership. These new riders are the fare-paying customers the MTA have been looking for this whole time, but right now, they’re all in their cars. Getting more drivers onto transit is essential for raising revenue, easing congestion, and having a greener, safer City.

Implement congestion pricing. The MTA can increase fare box revenue for operations and bring in revenue for new capital projects at the same time. How? Implement congestion pricing. On top of raising billions for the MTA to complete projects like installing subway platform doors or finally bringing the system to full ADA compliance, 64% of drivers said they would switch to transit if congestion pricing were implemented.

Push for more federal funding for transit operation. Throughout the pandemic, the CARES Act supported the operations of transit agencies throughout the country with emergency funding, mainly to fill the fiscal gap left by plummeting transit ridership and subsequent decline in fare box revenue. While the influx of funds came in response to a pandemic, it raised questions around the federal government’s overall role in funding public transit and whether transit agencies, DOTs, and elected leaders should be pushing for dedicated funding from the Federal Transportation Administration to provide fast, reliable public transit service throughout the country.

Expand the Fair Fares program. Okay, this one isn’t exactly an operating revenue stream, but is still a tool at our disposal that can reduce instances of fare evasion that stem from folks not being able to afford transit. NYC funds the program, which provides half-fare MetroCards to eligible New Yorkers living below the federal poverty line, which is currently $27,760 a year for a family of four. We can cut down on fare evasion without resorting to punitive measures by expanding the Fair Fares program so that New Yorkers above the federal poverty line, but are still living in poverty by NYC standards, can qualify. We should also double down on outreach efforts to increase the number of eligible riders that apply for the program, which is abysmally low with estimates reporting roughly half of eligible New Yorkers haven’t applied for the program.

Point is, it seems the MTA is determined to do all they can to punish and deter fare dodgers, but the goal should be reducing how deeply, existentially reliant the continued survival of this vital public service—again, the nation’s largest, most expensive transit system—is on every single rider coughing up $2.75 without fail.

Derrick Holmes (derrick@ridersalliance.org) is Riders Alliance’s Digital Strategist.